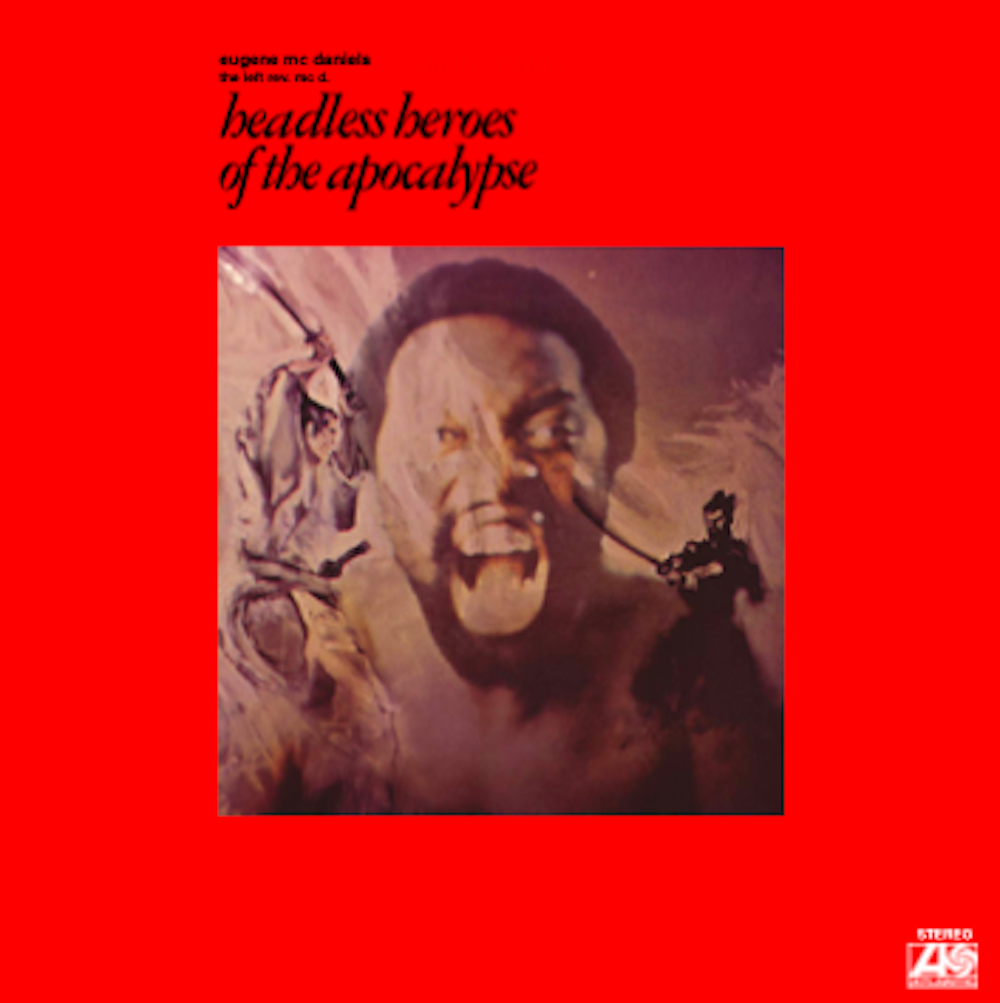

Fifty years later, Eugene McDaniels psychedelic soul-jazz awareness release, Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse, is more relevant than ever

Link: Real Gone Music

The year 1971 was a powder keg for social and political issues surrounded by the fact checkers of pop culture. Music had become more of an awareness art to expose the societal injustices and rebel against bad policy. Gil Scott-Heron released Pieces of a Man, while Nina Simone crafted the album Here Comes The Sun. Sly and the Family Stone exploded with There’s a Riot Going On and Isaac Hayes came out with Black Moses. The truth was out there and that concept of “truth” most evident in the words of Eugene McDaniels. He risked everything to be the “truth” prophet with Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse.

A soul-jazz songwriter throughout most of the 1960s, Headless Heroes became one of the more obscure and interesting releases of the era.

I had discovered the album years ago through some random library crate digging. I found the songs within to be peculiar yet strangely fascinating. The album became an eye-opening experience. In a word—unforgettable. The blatant honesty and cult-like demeanor of McDaniels lyrical prose did not match up to the black hero worship of Shaft, released in the same year. Yet, comparing the two is like comparing Bruce Lee to Akiro Kurosawa.

More on the ideology behind Eugene McDaniels’s songwriting

On Headless Heroes, McDaniels was not shy in challenging himself in outdoing his already charged songwriting as he spent years exposing the realities of what was going on at the time. In 1966, he carved out lyrics like, “The President, he’s got his war / Folks don’t know just what it’s for,” lashing out at Lyndon B. Johnson for his political actions. Looking back, you can appreciate it for deepening a churning philosophy that led to the hippie movement. The song was later adapted as a charge against Richard Nixon who continued to convolute the decisions and insecurities of war and society.

This led to the recording of Outlaw in 1970. The album was his treatise on class analysis and illuminated its injustices. Then came Headless Heroes and McDaniels’s brazen focus on racial inequality. Because of the album’s pointilated attack on the Nixon era, Atlantic dropped him after getting attention from The White House for his verbal slashings. Had McDaniels gone too far or not far enough to reach more people?

Political and Racial Issues in Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse

When McDaniels took a shot in early 1971 with “Tell Me Mr. President,” the song explicitly points out the government’s inability to reach civility. The lyrics are a hint into the grandeur statement of the title track within Headless Heroes. He points out political extremism (“political pawns in the master game”); not one side is spared.

That awareness weighs a ton as he lays down lyrics like a handbook for ethical treatment. The chorus is a call-to-action that would drive any woke initiative and should be incorporated into modern-day ethics and civility discussions. For those who listened to it at the time, McDaniels’s soberingly honest observation is about as punk as it gets many years prior to the launch of the movement.

“At last I had a chance to say what I believed in my deepest heart about politics, slavery, and about the genocide of Indians,” he said about the album. What he seems to have left out was his views on women’s rights which got blended into an overall viewpoint on equal rights.

“The Lord Is Back” is a weave of deep funk rhythms churned out by Weather Report bandmates Alphonse Mouzon (acoustic bass) and Miroslav Vitous (drums). The rest of the line up includes Harry Whitaker (piano), Gary King (electric bass), Richie Resnikoff (guitar), and Carla Cargill (female vocals).

In the song, he spices up a rooted foundation in Christian thought and an evolution of The Book of Revelations (given the times, it was not uncommon) to create this prophecy and new perspective that the Lord is black and boy is he here for vengeance. Add in a slight nod to environmentalism and McDaniels captures the essence of everything that was going on at the time. “The Parasite” goes even further in critique while also pointing at the injustices of indigenous people.

Headless Heroes was ground zero, even with a song as infantile as “Supermarket Blues.” Listen closer, and it’s an early testament to the realities of racial profiling.

McDaniels Continued Influence

McDaniels influence continued with Roberta Flack’s early 1970s releases with McDaniels’s “Feel Like Makin’ Love” being the pinnacle. Later, everyone from The Beastie Boys to A Tribe Called Quest pillaged McDaniels work as a nod to his genius.

Even today, people from Vernon Reid to Chicano Batman contribute testimonials in Real Gone’s 50th Anniversary of Headless Heroes release. The label expressingly takes great care with this reissue and are true heroes in keeping the vitality of this powerful statement alive and well within today’s pop culture. Headless Heroes is one that every single person on this planet should own and often explored, then re-explored. These songs are universal truths that correlate to today’s political and racial climate.

The saying ‘for evil to flourish good men need only to do nothing’ is as prevelent today, maybe more so than back in Gene McDaniels day. He was a true hero and had the courage to stand for his beliefs.

He never lost his own humanity during what were very parlous time for Coloured people in America.

We also have huge problems today in Australia, and there is a huge divide between white’s and coloured’s. Lip service is paid but little is achieved., I dont know the answer, but we need many more to have the courage lhat Gene displayed to reach out and try to bring awareness to others.

BTW I am a 76 year old white guy.